THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA

THE INDUSTRIAL COURT OF UGANDA HOLDEN AT KAMPALA

LABOUR DISPUTE CLAIM NO. 155/2014

(ARISING FROM HCT-CS-No. 303/2012)

BETWEEN

MWAKA MOSES............................................................... CLAIMANT

AND

ROAD MASTER CYCLES (U) LTD....................................... RESPONDENT

BEFORE

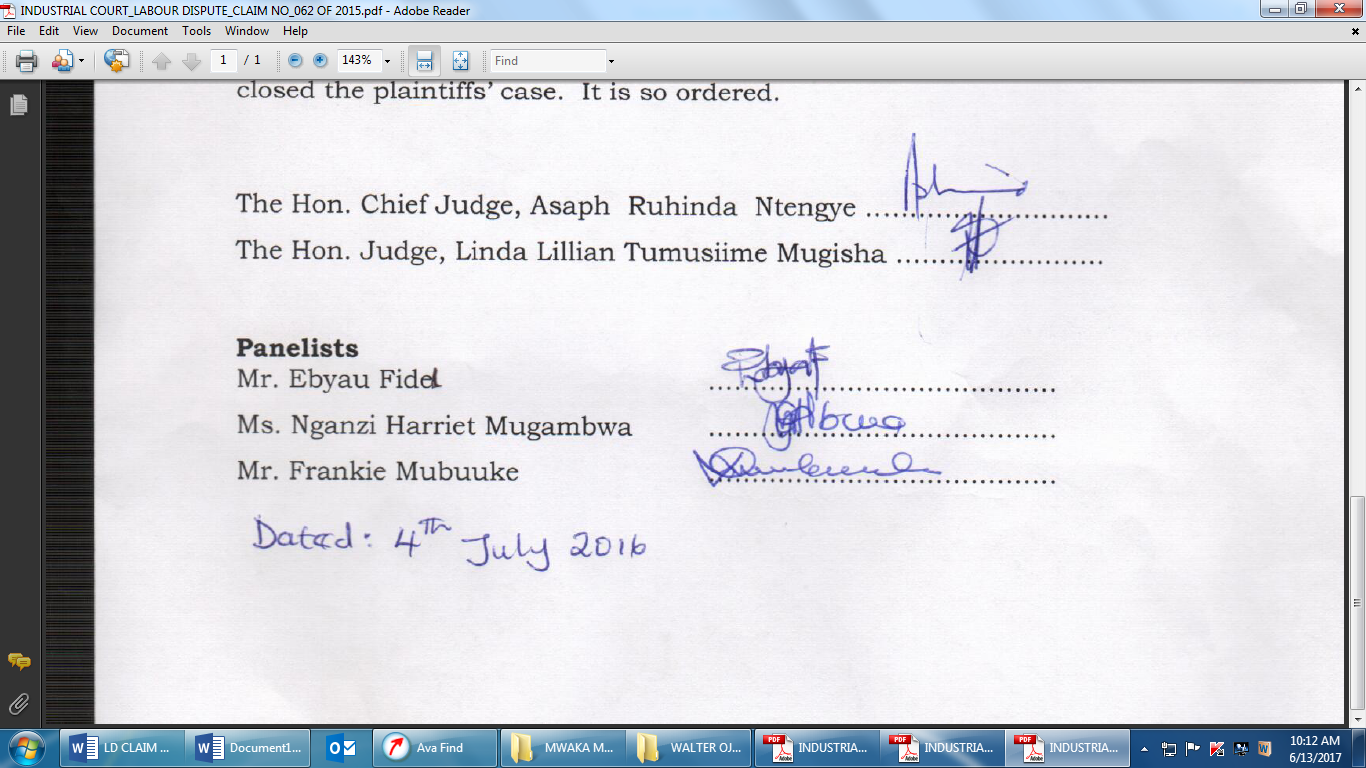

1. Hon. Chief Judge Ruhinda Asaph Ntengye

2. Hon. Lady Justice Linda Tumusiime Mugisha

PANELISTS

1. Mr. Ebyau Fidel

2. Ms. Harriet Nganzi Mugambwa

3. Mr. F.X. Mubuuke

AWARD

FACTS

This is a claim filed by the claimant claiming that having been employed by the respondent, the latter unlawfully terminated his employment.

By a memorandum of claim filed in this court on 28/1/2015, it was alleged that the respondent unfairly and unlawfully terminated the services of the claimant without justifiable reason and without any notice or payment in lieu of notice. It was also alleged that as a result of the unlawful termination, the claimant suffered loss and damage.

The claimant therefore prayed the court to grant:

Terminal benefits

Interest

General damages

Costs

Any other relief

By reply the respondent filed a response to the claim on 2/2/2015 denying ever terminating the services of the claimant but instead contending that the claimant absconded and abandoned his employment. This being the case, the respondent stated in the reply that the claimant was not entitled to any of the reliefs suggested.

The record does not possess any dismissal or termination letter. It was the claimant’s case that he was orally terminated by the Executive Director who told him to handover all the files of the respondent company which he did and made a report.

The case for the respondent was that when the claimant indicated he needed a salary increase, the Executive Director of the respondent explained that the company was going through a bad financial period and that as such increment of salary was not possible. According to the respondent, it was this failure to increase salary of the claimant that caused him to abscond and abandon work.

Issues

Agreed issues were: -

Whether the claimant was unlawfully dismissed by the respondent from his employment?

What remedies are available for the parties?

Submissions

It was submitted on behalf of the claimant that the communication of termination of employment to the claimant was done orally just like other communications in the respondent company had been done before. It was also submitted on behalf of the claimant that an attempt to settle the matter on the part of the respondent showed an admission that the respondent had in fact terminated the claimant’s employment. Counsel argued that the letters addressed to counsel for the claimant denying termination and calling the claimant to work were a hoax one Kajubu Charles having been forced to write them after the verbal termination of the claimant.

In his submission, despite the letter written denying termination and calling the claimant to work, the claimant could not attempt to go to work after being exposed to “such harsh, embarrassing, and callous behaviour by his employers........”

The respondent on the other hand submitted, through legal counsel, that the claimant just abandoned work after the respondent had not considered an increase in wages when management decided to give him additional assignment in the belief that the he had been underutilized.

Evaluation of evidence and the law applicable

The claimant’s case rests on the contention that the respondent terminated his employment which the respondent denies. The question therefore is did the respondent in fact terminate the employment of the claimant?

Section 65 of the Employment Act provides for circumstances under which termination of employment is deemed to exist.

It provides:-

“65 Termination”

Termination shall be deemed to take place in the following instances.

Where the contract of service is ended by the employer with notice.

Where the contract of service, being contract for a fixed term or task, ends with the expiry of the specified term or the completion of the specified task and is not renewed within a period of one week from the date of expiry on the same terms or terms not less favourable to the employee.

Where the contract of service is ended by the employee with or without notice, as a consequence of unreasonable conduct on the part of the employer towards the employee, and

Where the contract of service is ended by the employee, in circumstances where the employee has received notice of termination of the contract of service from the employer, but before the expiry of the notice.

The date of termination shall, unless the contrary is stated, be deemed to be

In the circumstances governed by subsection 1(a), the date of expiry of the notice given.

In the circumstances governed by subsection 1(b), the date of expiry of the term of completion of the task.

In the circumstances governed by subsection 1(c), the date when the employee ceases to work for the employer and

In the circumstances when an employee attains normal retirement age.

The above section of the law, in our view provides for the legal circumstances or methods that may culminate into termination of employment. Before any party to the proceedings proves unlawful termination, evidence must be led to prove first the fact of termination thus proving either of the scenarios mentioned in the above section of the law.

It is our considered opinion that since it was the claimant who contended that he was terminated, the burden lay on him to prove either of the circumstances in the said section of the law.

In his submission, counsel for the claimant seemed to argue in general terms that the claimant was terminated by pointing out the circumstances under which the claimant stopped working. Yet in our view, counsel should have specifically provided court with which method or circumstance under section 65 of the Employment Act, such termination occurred.

It seems to us that the reason that the law provided for a specific law was to avoid situations where in fact no termination of employment occurred, like it is alleged in the instant case by the respondent. In other words the mere stopping to work by an employee in circumstances other than those in the said section, may not amount to termination of employment.

Be that as it may, given the provisions of the above section of the law, and given the evidence adduced by the claimant, we form the conclusion that the alleged form of termination is under section 65(c) of the said law. This is because of the following reasons:

It was the claimant’s evidence that the Executive Director on 15/05/2012 informed him to handover all files which he did and he made a report. The insinuation of this state of affairs is that the claimant had committed no breach of the employment relationship or any fault whatsoever and that therefore the act of directing him to handover was unreasonable conduct within the meaning of section 65(c) of the above cited law. It can also be safely said that according to the claimant, the fact of denying him entry to the premises on 16/05/2012 constituted unreasonable conduct within the said section of the law.

The court record contains written communication about additional assignments to the claimant. In one of the letters dated 27/01/2012, the claimant asked the Executive Director for a job description and on 10/05/2012 the Personnel Officer provided the Job description without anything to do with additional pay although on 1/10/2011, the claimant had asked whether the additional assignment had any financial implication as regards remuneration.

On the record also is a handwritten document dated 15/05/2012, suggesting a kind of handover by the claimant. On 24/5/2012 M/s. Musamali & Co. Advocates issued a notice of intention to sue to which the respondent denied ever terminating the services of the claimant. Earlier on, 22/052015, the Personnel Officer of the respondent had written to the claimant demanding explanation as to why he, the claimant had not worked from 16th May 2012.

Although the testimonies of the respondent seemed not to mention, it seems to us that the origin of the conflict between the parties emanated from the assignment of additional duties to the claimant by the respondent. We tend to agree with the submission of counsel for the respondent that after being assigned additional duties without the requisite additional wages, the claimant felt aggrieved. We think that as a result a rift emanated and two possibilities happened.

The first possibility is that the respondent informed the claimant that if he did not want to do the extra duties at the same wage, he could leave the job and therefore asked the claimant to handover and leave the company.

The second possibility in our considered view is that the claimant having been aggrieved, decided to put down his tools and handover to the respondent.

We believe that either of these possibilities happened at a meeting attended by the executive director and the personnel officer although the evidence does not show exactly what happened at that meeting and the tone of the meeting. It is however clear that immediately after the meeting there was a hurried handover by the claimant.

We do not accept the submission of counsel for the claimant that the letters written by one Kajubu Charles, the Personnel Officer of the respondent, were properly explained and disapproved by his testimony that purported that he had been forced to issue and authenticate them.

On the contrary we agree to the submission of counsel for the respondent that where oral testimony is at variance with documents authored by a witness documentary evidence should be given more weight. Whereas in Kajubu's testimony in court he informed court that in a meeting he attended, the Executive Director informed the claimant that he had been terminated for disobeying orders and indiscipline, he himself authored a letter as Personnel Officer to the claimant demanding to know why he had absconded from duty. He also authored letters to counsel for the claimant after a notice of intention to sue, denying that the respondent had terminated the services of the claimant. His evidence that the executive director orally dismissed the claimant and asked him to collect his terminal benefits after a handover was sharply contradicted by a letter he himself authored denying termination and questioning the failure of the claimant to report on duty.

We are not satisfied that the Personnel Officer was under duress or intimidation so as to contradict the position he believed was the correct position. He is therefore not a reliable witness for the purpose of proving that in fact the respondent terminated the employment of the claimant, later on in accordance with section 65 (c) of the Employment Act.

We consider whatever transpired at the meeting to be the determining factor as to whether the claimant stopped working in circumstances covered under section 65(c) of the Employment Act. Was the conduct of the respondent so unreasonable that the claimant had no alternative but to stop working?

This court in the case of Nyakabwa J. Abwoli vs Security 2000 LTD, LDC. NO.108/2014 had this to say:

"In order for the conduct of the employer to be deemed unreasonable within the meaning of section 65(c)..... Such conduct must be illegal injurious to the employee and make it impossible for the employee to continue working. The conduct of the employer must amount to a serious breach and not a minor or trivial incident and the employee must act in response to such breach not for any other unconnected reason and act in reasonable time. What might be a serious or major breach in one case may not be necessarily major in another case so each case must be decided on its particular facts."

This court in the above case after analyzing the conduct of the employer held:

"Once the employer removes the instruments of an office for which the employee is employed to occupy and instructs another employee to take up such instruments without providing an alternative to the employee such act constitutes termination of employment by reason of the employers conduct. such termination is referred to as constructive dismissal............the fact of the claimant leaving his job was in response to the unilateral removal of the instruments of his office and giving them to other employees rendering him jobless.......this amounted to constructive dismissal or termination of contract in accordance with section 65(c) of the Employment ACT."

whereas in the above case evidence was led to show that the claimant was abused by a quarrelsome employee before the said employer removed all the instruments of the office from him, in the instant case the only evidence as to what transpired in the meeting was insufficient to enable the court draw any conclusions. The only witness contradicted himself as already noted. We do not find any evidence to support the submission of counsel for the claimant that his client had been exposed to" harsh, embarrassing and callous behaviour of his employer" ,the reason he gives for not returning to work despite the respondent's offer. Although in the above case just like in the case before us, the claimant left the job and the respondent denied terminating him, the court in the NYAKABWA case was convinced that given the circumstances under which the claimant left, it was not safe for the claimant to return to work since the respondent had assigned his duties to his junior and given the character of his boss. The court was convinced that there was no job for the claimant. It is our position that without a detail of what transpired in the meeting and the evidence of the personnel officer having been declared unreliable, what is left is only the handover report. Unfortunately for the claimant, this report by itself without evidence of termination is not sufficient because a mere handover to an employer is no evidence that such employee has been terminated. As already alluded to, it could have been that in the meeting both parties disagreed on the additional pay and the claimant decided to leave the job thus the hurried way of handover.

The evidence of the gate keeper of the refusal of the respondent to allow the claimant into the premises is also a lame duck without the evidence of termination by the respondent which was only from the personnel officer

The same applies to the evidence of the claimant that the respondent tried to force him into accepting a settlement by taking terminal benefits which according to him were not sufficient. This settlement was denied by the respondent and since it was not signed and there was no other evidence to corroborate that of the claimant, our view is that it serves no useful purpose in as far as establishing that the claimant was terminated.

The reaction of the respondent after a notice of intended suit was served in our view depicts a reconciliatory approach which the claimant was not prepared to accept.

We find the refusal of the claimant to return to work after being invited as evidence of the possibility that the claimant was not satisfied with the terms under which he was to get additional assignment.

It is our view that ordinarily, the claimant would have proceeded to his workplace following the letter denying termination of his services which letter was written only nine days after the alleged dismissal.

It would be the reaction of the respondent after an attempt to resume his duties that would in turn determine whether the claimant was in fact dismissed by the respondent and it is this reaction that would determine the unreasonableness of the employer within section 65(c) of the Employment Act. The claimant claimed he did not return because he had been exposed to harsh, embarrassing and callous behaviour by the respondent. The court as already mentioned finds no evidence of this behaviour.

From the claimant’s evidence, the respondent verbally dismissed him in a meeting whereupon he, the claimant made a report and handed over the keys. The only evidence that the respondent asked the claimant to handover was from one Baliddawa who testified that he heard one Pawan ask keys from the claimant. As already intimated, this could have been because of the dispute over wages for additional work. Therefore without evidence as to what exactly happened in the meeting, this is not sufficient to prove termination. In the absence of evidence that it was the respondent who asked the claimant to make a report, and in light of the evidence that the respondent communicated to deny the dismissal and to ask the claimant to resume his duties, which the claimant refused, we find that the fact of termination of employment under section 65 of the Employment Act has not been proved.

We hold that the claimant having been aggrieved about his extra assignment at no extra pay, developed misunderstandings with his employer and left the work place but the respondent as his employer called him back to resume work which he refused. We do not consider this as termination of employment on the part of the respondent as counsel for the claimant wants this court to believe. In our considered opinion there was a disagreement over pay for additional work which we think was genuine and the claimant stopped working in circumstances that we consider as a resignation and not a termination. We form the opinion that the claimant attempted to turn a resignation into a termination so as to benefit as an unlawfully terminated employee and this is not acceptable to us. At the same time we condemn any attempts by any employer to suffocate an employee in the demand for additional pay for additional assignment depending on the circumstances. The first issue is resolved in the negative.

The second and last issue is what remedies are available?

Having ruled that the claimant was not terminated, it follows that he will not be entitled to remedies like general damages, gratuity, payment in lieu of notice and severance. However, the claimant worked up to 15th of May 2012 and he is entitled to fruits of his labour for this period.

The evidence of the respondent shows that it was the practice of the respondent to pay leave allowance to the workers at the end of the year. Indeed evidence was led to show that workers including the claimant received leave encashment for the years 2005 and 2011 although the claimant denied that this was leave encashment. He instead argued that it was bonus which we do not accept as it is clearly shown and signed for as leave encashment.

We however do not see any evidence of encashment of leave for any other period. The respondent argued that documents of encashment of leave were in the custody of the claimant who never handed them over to management when he abandoned the office. We do not accept this argument because

it was the responsibility of the respondent to show the court that the respondent was paid his leave according to the existing practice of paying in lieu of leave at the end of the year. The respondent imputed that whoever did not take leave was paid at the end of the year in lieu of leave. Having tendered evidence that the claimant was paid for 2005 and 2011 it was upon the respondent to adduce evidence that either the claimant took his leave for the rest of the period or he was paid in lieu of leave. Ordinarily an employee is expected to apply for leave and chose either to take it or be paid in lieu and if he does not apply for leave when he is aware of his right of leave , the presumption is that he has voluntarily denied himself leave and he cannot claim it unless his employer consents to it, see NYAKABWA J. ABWOLI VS SECURTY 2000LTD(SUPRA).

In the matter before us it was the policy of the respondent to pay leave at the end of the year and the requirement of the claimant to show that he applied and was denied leave does not apply especially in view of the fact that the respondent submitted that they paid him but he was in possession of the documents. It is our considered view that if the encashment documents of the rest of the years existed the respondent would have been in position to produce them the way they produced the 2005 and 2011 documents. In the absence of the same we are constrained to hold that the claimant was entitled encashment in lieu of leave for the period 1999 up to 2012 excluding the years 2005 and 2011 which were paid.

We have not seen evidence to justify repatriation allowance or other prayers in the claim. We therefore find:

1) The claimant's employment was not unlawfully terminated

2) The claimant is entitled to wages from 15th may to end of May 2012

3) The claimant is entitled to leave encashment for the years 1999, 2000,2001,2002,2003, 2004, 2006, 2007,2008,2009,2010

4) The sums payable will attract interest of 20% per annum from the date of award till payment in full

5) No order as to costs is made.

SIGNED

DATED: 09th /March/2017