THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA

THE INDUSTRIAL COURT OF UGANDA HOLDEN AT KAMPALA

LABOUR DISPUTE CLAIM. NO 146 OF 2014

(ARISING FROM HCT CS- 226 OF 2012)

BETWEEN

JOHN TUSHABOMWE........................................................ CLAIMANT

AND

EQUITY BANK LTD....................................................... RESPONDENT

BEFORE

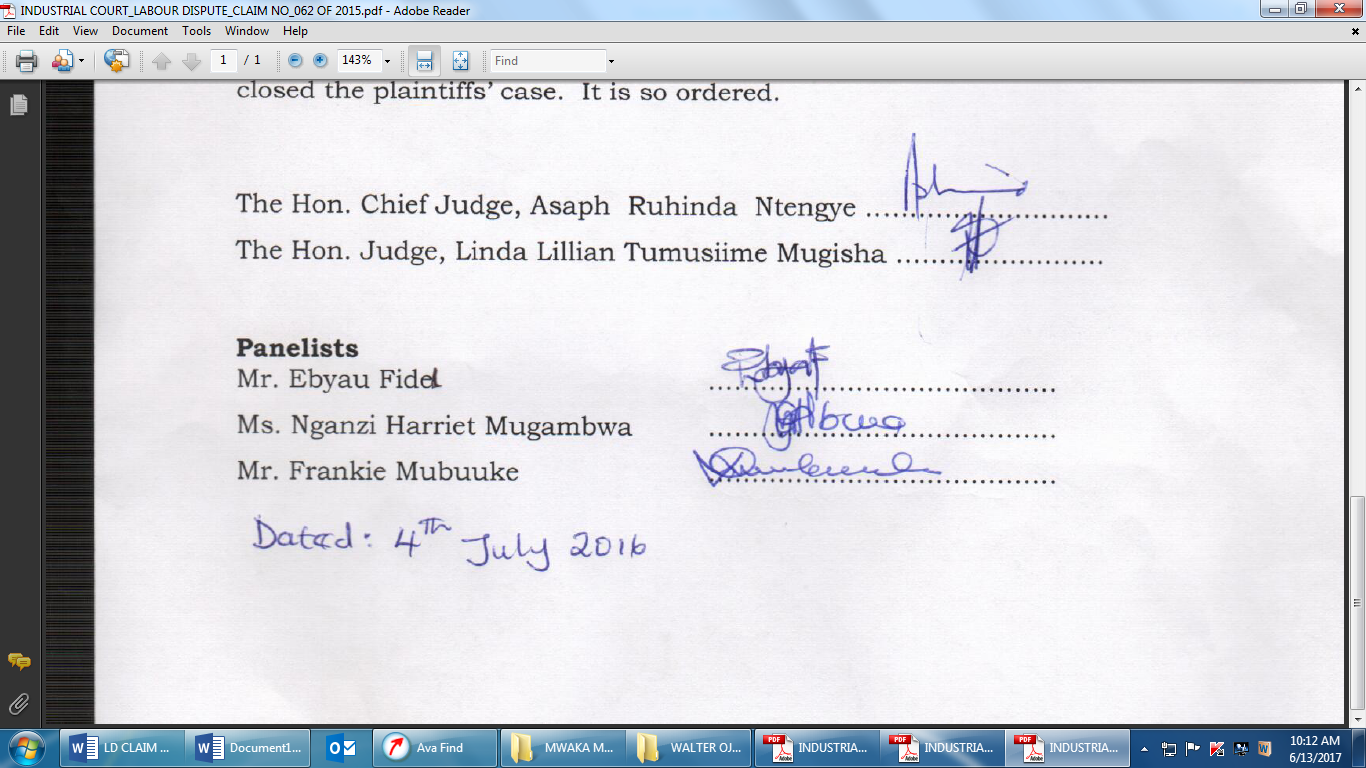

1. Hon. Chief Judge Ruhinda Asaph Ntengye

2. Hon. Lady Justice Linda Tumusiime Mugisha

PANELISTS

1. Mr. Ebyau Fidel

2. Ms. Harriet Nganzi Mugambwa

3. Mr. F.X. Mubuuke

AWARD

This claim originated from the High court, civil Division and it was originally registered as Civil Suit No. 226/2012.

The following facts were agreed by both parties;

That on 26/10/2009, the claimant was employed by the respondent and was subsequently promoted to head of Business Growth and Development on 22/09/2016.

That on 24/03/2013, the claimant resigned from employment.

That the respondent accused the claimant of negligence in performing his duties in respect of a loan account of one Luyiga Geoffrey.

That the respondent has not paid the claimant accrued salary benefits under the provident fund and neither has the respondent issued to the claimant a certificate of service.

From the documents available and from the evidence of both the claimant and the respondent, we form the opinion that the case for the claimant is that the respondent without good cause refused to give him the exit clearance after he had properly tendered his resignation and as a result he was denied his salary and other benefits.

On the other hand the case for the respondent is that, although the claimant had tendered his resignation, he in the course of his duty had been negligent and as a result the banks incurred financial loss (or potential loss) to the tune of 7,000,000/= and the claimant could not be paid benefits unless he made good the loss occasioned.

The agreed issues as shown in the joint scheduling memo filed in the High court are:

Whether the claimant was negligent in handling the loan account of one Mr. Luyiga Geofrey.

Whether the decision by the respondent to withhold the claimant's salary and accrued benefits was lawful.

Whether the respondent’s refusal to issue a certificate of service to the claimant was justified.

What are the remedies available to the parties?

In an attempt to resolve the above issues, each of the parties adduced evidence from one witness and also filed relevant documents.

Let us now deal with the first issue that alleges negligence on the part of the claimant.

We have perused the evidence in chief of the only witness of the respondent. We do not find any evidence suggesting that the claimant was negligent during employment. The evidence in chief is about the entitlements of the claimant. It only disputes what the claimant claims as his benefits.

However in cross examination, the respondent revealed that the benefits of the claimant had not been paid because he had not completed the clearing process.

In his evidence the claimant testified that once one Luyiga Geofrey failed to clear the loan, he and another issued a demand notice to one Mirembe Justine, the guarantor of the loan, who in turn paid the money into the loan account. This evidence was not disputed. According to the claimant since the network was unstable, this money was not immediately recovered and when the network was stabilized and an attempt was made to recover the money from the account, the clearing department of the respondent had already cleared a cheque that had been issued by the said Luyiga and therefore the money was not available to clear the loan. The matter was forwarded to the legal department which produced a legal opinion that did not in any way implicate him in negligence.

It was his evidence in cross-examination, that when the money was deposited into the bank account, he gave instructions to his credit officer to put a lien on the account as an additional safeguard to the internally generated system. In his submission, counsel for the claimant contended that the claimant was in no way to blame for non-recovery of the loan, the legal officer having not imputed negligence on his part and the respondent having thereafter appreciated the claimant’s services by offering him a promotion and a salary increase. He argued that the claimant having not been subjected to disciplinary proceedings, the respondent could not turn around and allege negligence since the claimant was not offered an opportunity to explain.

He submitted that none recovery of the loan was due to lack of coordination and team spirit on the part of the respondent departments which could not be visited onto the claimant as an individual.

In reply counsel for the respondent contended that the claimant was negligent in handling the credit facility in the account of one Luyiga. He argued that the claimant’s conduct of leaving the money onto the account without registering a lien overnight and trying to apply it on the loan the following day amounted to negligence.

He contended also that the fact that the claimant left his junior to place a lien so as for him to visit another person’s sick child in hospital was negligent of the claimant.

He argued that it could not have been as a result of the unstable electronic system that the money was not applied to the loan since it was the same system that cleared the cheque on the same account. Counsel relied on the authority of BLYTH VS COMPANY PROPRIETORS OF THE BIRMINGHAM WATER WORKS CO. (1856) 11 EXCL. 781 and ARIM FELIX ALIVE vs STANBIC BANK OF UGANDA LTD HCCS O237/2010.

In rejoinder counsel for the claimant argued that allegations of negligence could not be sustainable one year after the claimant had left the bank. He relied on section 62(5) of the Employment Act. He also argued in rejoinder, that the finacle system of the bank having been on and off, it was only when the system would stabilise that the money would be recoverable and this could not be blamed onto the claimant.

He submitted that the claimant only visited the sick patient in the evening after working house and therefore there was no negligence exhibited.

In the above two cases the test of a reasonable person was held to be crucial in the law of negligence. It is this test that provides for a standard by which a person’s conduct is judged and this always depends on the circumstances of each case.

Thus “a defendant will be negligent by falling below the standards of the ordinary reasonable person in his or her situation i.e. by doing something which a reasonable man would not do, or failing to do something which the reasonable man would do.”

The claimant was a manager in the credit sector. He did everything possible to recover the loan and indeed the loan was recovered and credited onto the account.

The evidence of the claimant that the finacle system was not stable at the time the account was credited was not challenged. It is only in submissions that counsel for the respondent argued that since the cheque (and may be other transactions in the bank) was cleared, the instability of the system could not have been a reason for the claimant not to immediately recover the loan. We respectfully do not agree.

The claimant testified that the finacle system was that evening on and off. This being the case, which ever activity that depended on the system could only be done as and when the system would stabilize. It is possible that at certain times certain activities would be done leaving others undone.

It is therefore not possible to conclude that just because the cheque was cleared, the system was stable and therefore the claimant should have immediately recovered the loan. On a balance of probability we agree with the claimant that it was not possible to immediately recover the loan because the system was unstable.

Was the claimant negligent when he visited the sick person having instructed his junior to register a lien? It was submitted by the respondent that the claimant abandoned the transaction to his junior and went on a frolic during working hours.

The claimant in his statement (PEX. 11) which was handwritten says

“on the evening she brought it, the system was on and off (finacle). One of our staff called Jackline Nafula had a sick child admitted to a clinic at Luzira. I left the client in the branch writing to deposit the money with my credit officer called James……………….. with instructions to put a lien on Luyiga’s account as soon as the money was deposited………….." The exact time that the claimant left the bank is not mentioned and neither is the exact time that the money was deposited onto the account.

It is clear however that the claimant left the bank in the evening before the money was deposited onto the account (because of the instability of the system.

We agree with counsel for the claimant that "evening" referred to by the claimant must have been after 5pm which was after working hours. Was it a reasonable act for the claimant to leave instructions to his junior and go visiting a sick patient?

The instructions were given to a credit officer working under the claimant. Since the finacle system was unstable and yet a colleague had a sick child in hospital, we think that leaving instructions to his junior who was qualified as a credit officer at the time to complete the transaction when the one banking the money was in the banking hall, did not constitute a negligent act. The credit officer was competent enough to register the lien as instructed. There was no evidence to suggest that the act of registering a lien was a preserve of the claimant without any power of delegation.

To suggest that the claimant should not have delegated his function and should have kept in the bank indefinitely waiting for the stability of the finacle system instead of delegating and visiting his colleague in hospital after office hours, would in the least be described as being insensitive.

Section 62(5) of the Employment Act 2006 provides that

“Except in exceptional circumstances an employer who fails to impose a disciplinary penalty within 15 days from the time he/or she becomes aware of the occurrence giving rise to disciplinary action, shall be deemed to have waived the right to do so.”

Although the kind of disciplinary penalty prescribed under the above section may not have been necessarily the one to be imposed upon the claimant, the section is an eye opener that disciplinary action of whatever kind ordinarily is taken against the offending employee within a reasonable time after commission of the disciplinable offence.

Negligence in performance of one's duty is a serious matter which in our view may be cause to institute disciplinary proceedings against the offender.

On perusal of the various documents exhibited, it is not disputed that whereas the questioned account was credited on 6/7/2010, the claimant officially resigned on 24/03/2012 and by this time the respondent had not raised any concerns regarding negligence on the part of the claimant.

Instead, the claimant had been promoted and his salary increased.

We agree with counsel for the claimant that if indeed the claimant had been negligent, disciplinary proceeding would have been brought against him during his tenure as an employee of the respondent and within reasonable time of the occurrence of the act that warranted disciplinary action within the meaning of section 62 of the Employment Act.

Although the respondent denied EXhb P4, the legal opinion concerning the matter, we want to believe that indeed an investigation must have occurred and a report produced. After denying this report which seemed not to blame the claimant, the respondent should have produced something else to suggest that the respondent indeed had blamed the claimant.

In the absence of this report, it is tempting to conclude that in fact the respondent never blamed the claimant in negligence and that the blame came up as an afterthought as the claimant processed his exit from the respondent’s employment having been offered employment elsewhere.

We do not think that the claimant breached his duty of care when in the circumstances of instability of the finacle system he delegated a competent credit officer to lay a lien on the account.

We agree with the claimant that failure to recover the loan was as a result of lack of coordination on the part of the respondent bank’s different departments which cannot be visited onto the claimant as an individual.

We therefore hold that negligence of duty was not proved and the answer to the first issue is in the negative.

The second issue is:

Whether the decision by the respondent to withhold the claimant’s salary and accrued benefits was lawful.

It seems to us that the question whether the claimant was entitled to benefits is not denied by the respondent. The issue for this court at this stage is – why did the respondent decline to pay the same?

In his submission counsel for the claimant argued that the claimant could not be paid his benefits simply because the respondent was still investigating the claimant’s role in the loan account of Luyiga, which according to counsel was illegal. He relied on section 43(6) of the Employment Act.

Counsel for the respondent argued in his submission that the claimant could not be paid the benefits because of the rigorous procedures of exiting the bank which procedures had to be complied with before the benefits could be paid which according to him was in good faith for the good of the institution and accountability on the part of staff.

He argued that the respondent offered to pay the claimant his benefits but the claimant declined. The respondent could not pay, according to him, because the claimant disputed the amounts due to him.

Section 43(6) of the Employment Act provides

“on the termination of his or her employment in whatever manner, an employee shall, within 7 days from the date on which the employment was terminated be paid his or her wages and any other remuneration and accrued benefits to which he or she is entitled."

It is not disputed that the claimant legally terminated his services with the respondent by resignation and that at the time of resignation there were no issues, capable of halting this kind of termination of employment

We appreciate the importance of an employee to complete the exit process as his employment comes to an end.

We agree with counsel for the respondent that it is not in bad faith that employers delay payment of terminal benefits pending completion of the exit process but it is for the good of the employer institution and accountability on the part of the employee.

That is the reason why in the case of OCHIENG JOSEPHAT Vs MONITOR PUBLICATIONS LIMITED labour dispute claim No. 206/2015 this court held that in accordance with section 43(6) of the Employment Act, once an employee’s contract terminates in whatever manner , he or she should be paid 7 days after the completion of the exit process. The court further held that the exit process ought to be completed within a reasonable time not exceeding three months.

In the instant case, it seems to us that the exit process was taking time for ever. The claimant having tendered in his resignation, the exit process should have started and been completed within a reasonable time so as for the claimant to access his terminal and other benefits. Instead, after receiving a letter from counsel for the claimant about his benefits, the respondent wrote in reply suggesting that the claimant misappropriated funds in respect to Luyiga’s account and that no clearing certificate would issue until he refunded the same.

As already discussed, evidence on the record does not show any misappropriation of funds. The evidence only alleges negligence on the part of the claimant and we have made a finding that the claimant was not negligent.

The record reveals that on 20/4/2014, the respondent communicated to counsel for the claimant about their willingness to pay certain amounts as benefits to the claimant which were disputed.

As counsel for the claimant submitted, this offer came 2 years after the claimant instituted the suit in courts of law and it is next to impossible for court to hold that this was reasonable time in the context of section 43(6) of the Employment Act as interpreted by this court in OCHIENG JOSEPHAT VS MONITOR PUBLICATIONS LTD (supra).

It follows therefore that the decision by the respondent to withhold the claimant’s salary and accrued benefits was not lawful and the second issue is decided in the negative.

The third issue was whether the respondent’s refusal to issue a certificate of service was justified.

Section 61(1) of the employment Act provides that once an employee on termination of service requests for a certificate of service, the employer is obliged to provide it to the employee.

This section in our view is intended to provide general information regarding the employee so as to enable the next employer assess the capability of the employee in the next assignment. It is also intended for satisfaction of the employee as to how he applied his knowledge and expertise at the assignment he/she just completed.

Therefore in our considered opinion, a certificate of service is an important document not only for the employee but for the prospective employer, the reason section 61(1) of the Employment Act provides for it.

The respondent argued both the second and the third issue together. In effect the same submission relating to the exit process applied to the third issue. We have already extensively discussed the exit process and pronounced ourselves on the same vis a vis payment of benefits. As the delay of payment of benefits was unlawful and so unjustified was failure to have a certificate of service to the claimant. The third issue is therefore resolved in the negative.

The fourth and last issue relates to remedies available.

The claimant argued that his salary had been unlawfully withheld and that the job he acquired was terminated as a result of the actions of the respondent and because of this he suffered emotional distress and anguish. He prayed for general damages, punitive damage, salary arrears, accrued benefits, among other prayers. He relied on DONNA KAMULI, FLORENCE MUFUMBA and RICHARD NDEMERWEKI.

General Damages

Counsel for the respondent argued strongly that the cases relied on by the claimant were not relevant to this case since they related to dismissal/termination of service whereas the instant case was about the claimant having resigned voluntarily and the legal actions having been based on the subsequent actions of the respondent after resignation.

He also argued that the claimant failed to prove that he lost his job in DFCU Bank because of the actions of the respondent. He argued that the findings on negligence and certificate of service had no bearing on the claimant’s employment in DFCU.

Whereas we agree with the submission of counsel for the respondent that the authorities cited by counsel concerned the unlawfulness of termination as applied to the instant case which is about the actions of the employer after lawful termination, we must say that the same authorities define what constitutes general damages.

We agree with the respondent that before court determines the question of damages, it must be satisfied that the respondent caused the damages.

We have made a finding that the claimant was not negligent, yet the respondent refused to pay him his benefits because they alleged negligence resulting in the loss or potential loss of 7,000,000/=. This accusation having come many months after the alleged loss or potential loss and after the lawful resignation of the claimant, in our view, was illegal and affected the claimant emotionally having been portrayed as a negligent and incompetent officer. He therefore deserves general damages.

As already discussed, a certificate of service is meant to offer a general picture about an employee so as for the next employer to appreciate the capacity of the employee to deliver on any assignment. The failure of the respondent to issue this certificate without good reason, affected the claimant negatively in securing or maintaining any job and in our view, this is reason for grant of general damages.

The unlawful withholding of the claimant’s benefits deprived him of using them for his personal benefit and development and therefore calls for general damages.

All in all, given that the claimant was at a managerial level and had prospective chances of employment which were thwarted by the actions of the respondent, we grant him general damages of 30,000,000/=.

We decline to grant punitive damages since they were not originally pleaded and prayed for in the memorandum of claim.

Salary arrears and provident fund

Whereas the claimant claimed 3,910,000/= as salary arrears, the respondent pointed out that given allowable deductions the claimant was entitled to 2,065,613/= and this was not contested in the submissions in rejoinder. We therefore allow 2,065,613/= as salary arrears due to the claimant. The same applies to the provident fund claim which is allowed at 3,544,445/=.

In conclusion we hereby enter an award in favour of the claimant in the following terms.

1) A declaration that the claimant was not negligent in handling the loan account of one Luyiga Geoffrey

2) A declaration that the respondent’s failure to issue the claimant with a certificate of service was illegal and unjustified.

3) The claimant shall be entitled to general damages of the sum of 30,000,000/= (thirty million shillings only).

4) The respondent shall issue a certificate of service to the claimant.

5) The respondent shall pay to the claimant 2,065,613/= as salary arrears.

6) The respondent shall pay to the claimant 3,544,445/= as provident fund contribution.

7) The respondent shall pay interest at 26% per annum on (5) and (6) from the date of filing the suit till payment in full and interest at 8% per annum on (3) from the date of this judgement till payment in full.

8) No order as costs is made.

Signed by:

DATED: 21ST APRIL, 2017

9